Matt Bidewell_

Rust and Referencing pt2

2021-01-17

This is part two of an intro to Rust and its ownership, referencing and borrowing model. Read part one here. Part one showed us that when a variable falls out of scope it is freed from memory. We then looked at who owns variables as they’re passed around int the code.

Referencing

With our knowledge of ownership and passing ownership to subroutines, we come across a new type of problem. What about when we want the parent function to retain the ownership of a variable? One simple solution is we return the initial variable but this gets messy and nasty. For example, the following code example is counter-intuitive.

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let (s2, len) = calculate_length(s1);

println!("The length of '{}' is {}.", s2, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: String) -> (String, usize) {

let length = s.len();

// return both the string and length

(s, length)

}

We’re returning the string and the length, but as a result, we need to declare a new variable back in the main function. It is not enough for code to just work, it needs to be readable as well.

Rust allows you to pass a reference to the variable instead. This allows the parent function to keep the scope of the original variable whilst allowing a child function to use it.

fn main() {

let name = String::from("Matt");

let len = calculate_length(&name);

println!("The length of '{}' is {}.", name, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: &String) -> usize {

s.len()

}

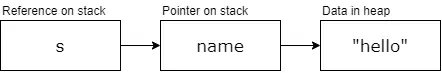

The clear difference in the code is the use of “&” when passing the variable to the function and in the function definition. The ampersands are called references and they allow us to refer to a value without transferring the ownership of it.

The “&name" syntax creates a reference of the value name but it does not own the value, this means when the scope is dropped in calculate_length Rust will not free the memory. In the calculate_length function, you’ll also note the &String type definition, this indicates the value is a reference.

Mutable reference

Having references as function parameters is called borrowing, you can imagine it as the function is borrowing the value and will give it back. However, what about if you tried to mutate the reference?

fn main() {

let name = String::from("Matt");

change_name(&name);

}

fn change_name(s: &String) {

s.push_str(" Bidewell");

}

This will cause the compiler to throw an error because, by default, all variables are immutable and so are their references. Instead, you need to specifically declare the reference mutable. So taking what we know about mutability we can make a tiny change to the code above to get the results desired.

fn main() {

let mut name = String::from("Matt");

change_name(&mut name);

}

fn change_name(s: &mut String) {

s.push_str(" Bidewell");

}

We have to change the variable to be mutable, the reference to be mutable and change the function definition to accept a mutable reference. There is, however, one restriction to mutable references, each variable can only have one mutable reference in scope. This restriction is purposeful as it allows a more controlled usage and helps to stop the chance of data race from happening at compile time.

A data race is similar to a race condition. It happens when two or more pointers access the same data at the same time, at least one of the pointers is being used to write data and there's no mechanism used to synchronize access to the data.

It's worth noting you CAN make multiple references in separate scopes, however, they can not exist simultaneously. Take the following code for example.

let mut name = String::from("Matt");

{

let newName = &mut name;

// do something with it.

// end of scope newName drops dead

}

let newName2 = &mut name;

In my opinion, this looks bad and is hard to follow in a larger code base and by managing your variables you shouldn't come across this issue.

One final rule to remember, you cannot have a mutable reference and an immutable reference in scope at the same time. The immutable reference would not be expecting its data value to change but with them both in scope its a possibility. Luckily the compiler will catch this and display an appropriate error message.

Summary

Referencing is a way to pass a variable to another function without having to change the scope of the variable. The compiler is also really good at catching memory-related errors and is ultimately there to help stop you writing bugs. We also need to remember that at any given time in scope you can have ONE mutable reference of a variable OR an unlimited number of immutable ones.