Rust and ownership

2021-01-10

Rust has grown a great amount in the past few years, so much that it was voted Stack overflow’s most loved language in 2020. Nearly 20% more than the runner up Typescript.

This two-part series will give a high-level overview of one of the main selling points of Rust; its lack of a garbage collector and its Ownership mechanism. We will cover the heap, the stack and variable ownership in part one. Part two will look at borrowing and referencing.

Background and Prerequisite

I come from a background of statically typed languages mainly Java before moving into the Node with Typescript world. I’m fairly new to the world of Rust and have only picked it up on the tail end of 2020.

Before we begin I’d expect you to have a firm understanding of at least one language and understand some concepts such as garbage collection and memory utilization.

Stack and Heap

In most high-level languages you’re abstracted away from knowing about the heap and the stack. The Stack and the Heap are temporary storage for a task. They both have some key differences which dictate when they should be used. advantages and disadvantages.

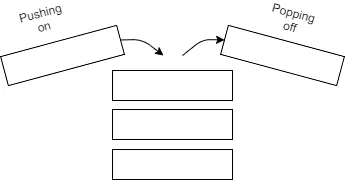

The stack stores data in a stack-like datatype which obeys the rules of last in first out (LIFO). Adding data onto the stack is known as pushing onto the stack and removing is known as popping off the stack. The data stored on the stack must be of a fixed size and not subject to any mutations.

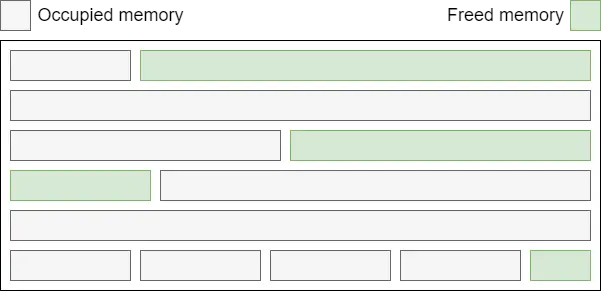

Data of unknown size or that can be modified is stored inside the heap rather than a stack. Data is dynamically stored inside the heap, your rust process will request some space and the memory allocator allocates a spot in the heap for your data. The memory allocator will then return an address which is the location of that data.

Pushing onto the Stack is much faster than dealing with the memory allocator as pushing onto the Stack doesn't require finding space for the data and then performing the necessary bookkeeping tasks to prepare for any subsequent allocations.

Popping off the stack is again much faster than dealing with the Heap. Instead, when you want to access the heap you have to follow a pointer to get to the location where your data requested is located.

Why is this important in the world of Rust? Well depending on whether the data is stored on the heap or the stack effects how rust handles its memory allocation and deallocation and ownership. For now, we should remember that dynamic data is stored in the heap whereas hardcoded data is stored on the stack.

Ownership and scope

Every value in Rust can only have one owner, when the owner of the value falls out of scope then the value is removed from memory. The scope is usually defined by curly brackets and in Rust, this is no different than most other languages.

fn sayHello() {

let msg = "hello";

// do stuff with msg

}

// msg now out of scope.

Usually, one of two things will happen. If the language has a garbage collector then that will free up that memory. If the language doesn’t have a garbage collector like C, instead you would have to tell your program to go deallocate the memory, this is to stop memory errors from happening in your program such as a memory leak.

Rust, however, approaches it from a different angle. Rust figures out when to deallocate memory at the compile time by identifying variables that are out of scope. Rust also finds memory errors such as leaks or accessing memory that is out of scope at compile-time and alert you.

The concept is pretty straight forward when the variable goes out of scope, rust will free that memory up. The Rust compiler adds the deallocation functions into the code for you.

fn sayHello() {

let msg = "hello";

// do stuff with msg

}

// msg now out of scope AND the memory has been freed in the heap

The concept seems simple and straight forward and it is. However, there are some situations where the behaviour of the code can be unexpected in more complex situations.

fn sayHello() {

let msg = String::from("hello");

let msg2 = msg;

// do stuff with msg2

}

// free msg memory

// free msg2 memory??

Note: We’re using String::from which forces our code to store the value in the heap.

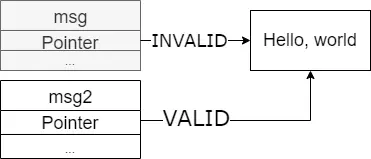

Here we assign msg to msg2, we then might think that when they go out of scope they should also both be deallocated from memory? Well not exactly. Both variables are pointing to the SAME bit of data, therefore when one of them goes out of scope you might expect the data to be freed, then when the second one falls out of scope you might expect an error. Rust is smart and overcomes this by invalidating the first variable pointer “msg”, at the time when you initialise the second.

Let’s look at another example:

let msg = String::from("Hello, world");

let msg2 = msg;

println!("{}", msg);

Here when we try to print msg we get an error saying “value has moved”. That's because Rust invalidates msg to stop you making a runtime memory error by deallocating the same data twice when it falls out of scope. Heres whats actually happening:

fn sayHello() {

let msg = "hello";

let msg2 = msg; // msg is now marked as invalid.

// do stuff with msg2

}

// msg is invalid

// free msg2 memory

As you can see, msg and msg2 are never pointing to the same data at the same time. Instead, Rust will invalidate the old pointer and leave only the newest, this solves the issue where msg2 would throw a memory error.

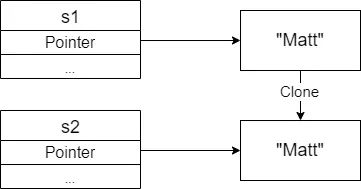

But what if you wanted to copy/clone some data? Well, Rust has a clone trait designed to do that. Traits are out of scope drum hit for this post. Just imagine them as a method that can be defined for any type.

let s1 = String::from("Matt");

let s2 = s1.clone();

s2 will point to a different data value than s1.

Ownership and functions

The functionality of passing variables to a function is similar to those rules for assigning to a value. For example:

fn main() {

let name = String::from("Matt"); // name comes into scope.

doSomething(name); // name moves into the functions scope.

// if we try to use name it would throw an error.

}

fn doSomething(myName: String) {

println("My name is {}", myName);

// myName comes into scope and is used.

} // myName is now dropped, including the data.

Here, “name” is passed into the function doSomething which is now the primary scope for that value. When doSomething finishes the initial data will be freed from memory, this can be an unexpected behaviour if you’re coming from a Javascript world. To be able to reuse the variable you might wish to return the value so you’re able to transfer the ownership of the variable back to the parent scope. So you could change the above code like so.

fn main() {

let name = String::from("Matt");

let name2 = doSomething(name);

}

fn doSomething(myName: String) -> String {

println("My name is {}", myName);

myName // myName is returned.

}

But this is a bit counter-intuitive and messy. Instead, Rust has a feature called References.